Found manuscript pieces over five centuries of age

“I lost my breath for a while, staring at the manuscript pieces,” says the antique book collector Eyþór Guðmundsson.

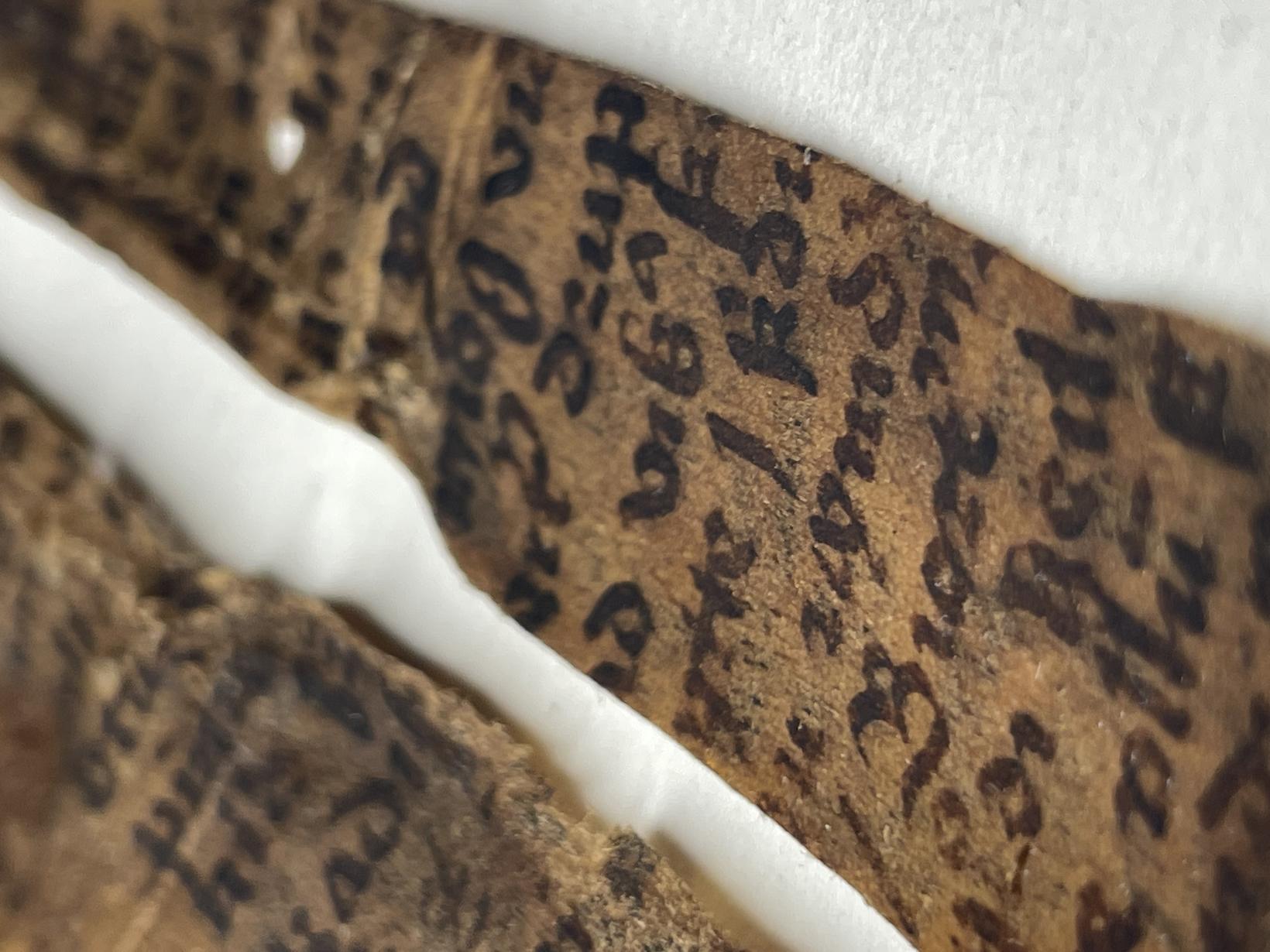

The account reveals the feeling that went through his mind when he realized that he had found fragments of an ancient leather scroll. The pieces were used as repair materials for a restoration of an ancient textbook.

It was later discovered that the pieces are estimated to be over 500 years old.

Owns almost 400 ancient books

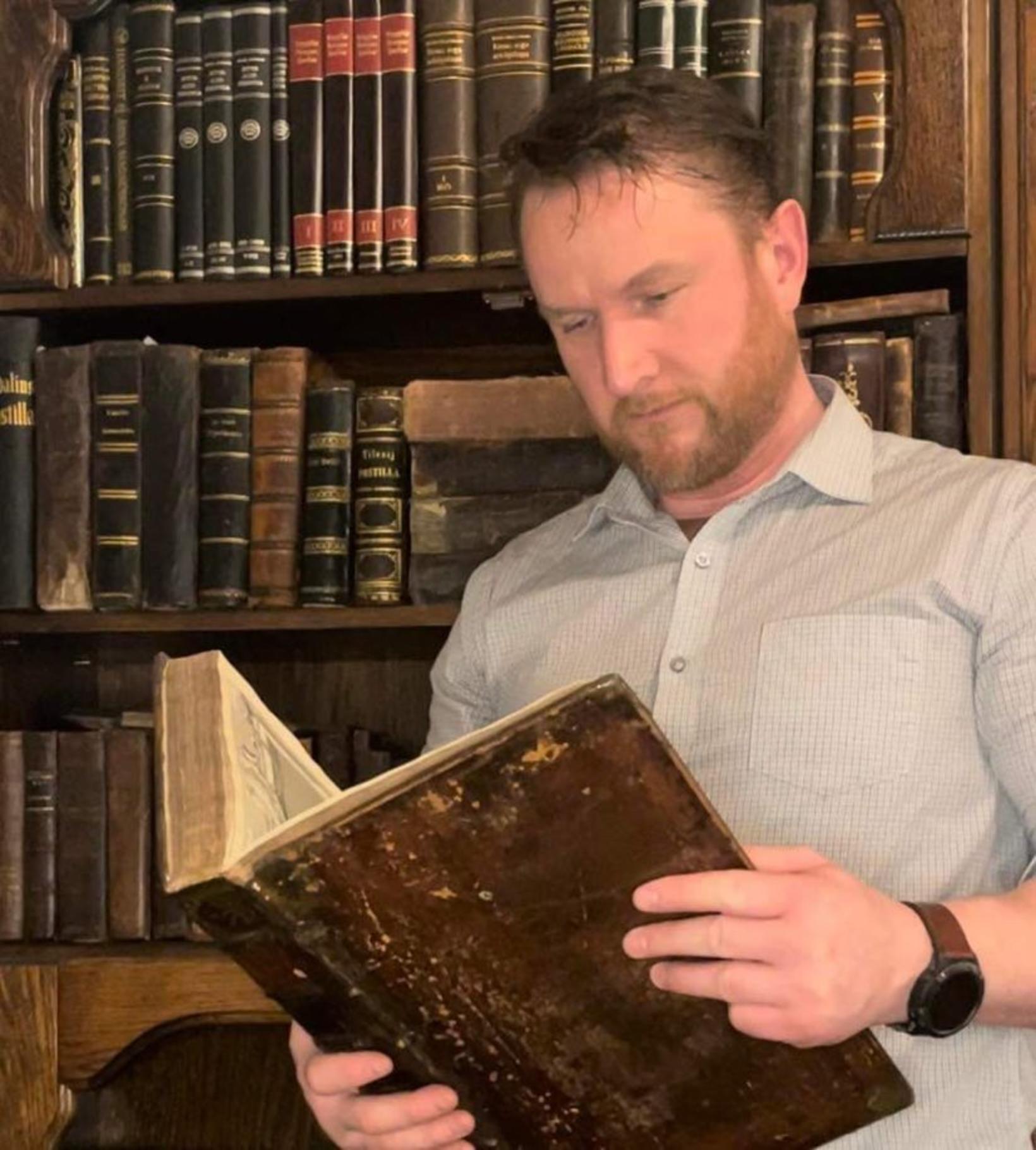

Eyþór has a collection of antique books, which counts almost four hundred titles.

“Most books I have are about 250 to 350 years old, and then I have a lot of books that are even older.”

Not only does he collect those books but he also restores them. He has bought or otherwise been rewarded with a number of books in bad condition, which he has both spent money and his time on to restore to their former glory.

Part of Guðmundsson's collection of antique books but he has almost 400 of them. Photo/Eyþór Guðmundsson

Has his Instagram page

Almost from the beginning of his life, his mind steered towards collecting antique books. Guðmundsson says that is simply how he is wired.

He says he sees it as one of his roles, as an antique librarian who focuses on Icelandic antiques, to ensure that the condition of the books is kept to the very best of their ability and as close to the original condition as possible.

For example, he says that he always makes use of the original leather of the books, but he has never had to have them tied into a new tape.

“I consider myself saving valuables, part of Icelandic cultural heritage.”

Guðmundsson maintains an interesting page on Instagram about his practice, Old Icelandic Books.

Don’t judge the book by its cover

Around three and a half years ago, Guðmundsson was restoring a book that had caught his attention at the store Bókakaffi or Book Café.

“I can always remember seeing this book. It didn’t look like much where it was among ancient textbooks, but I thought the cover was special.

After handling and scrutinizing it for a while, I decided to invest in and buy the book."

Here, Guðmundsson is talking about the original German edition of Evangelia Præfigurata by the theologian Reinhard Bake, and he goes on:

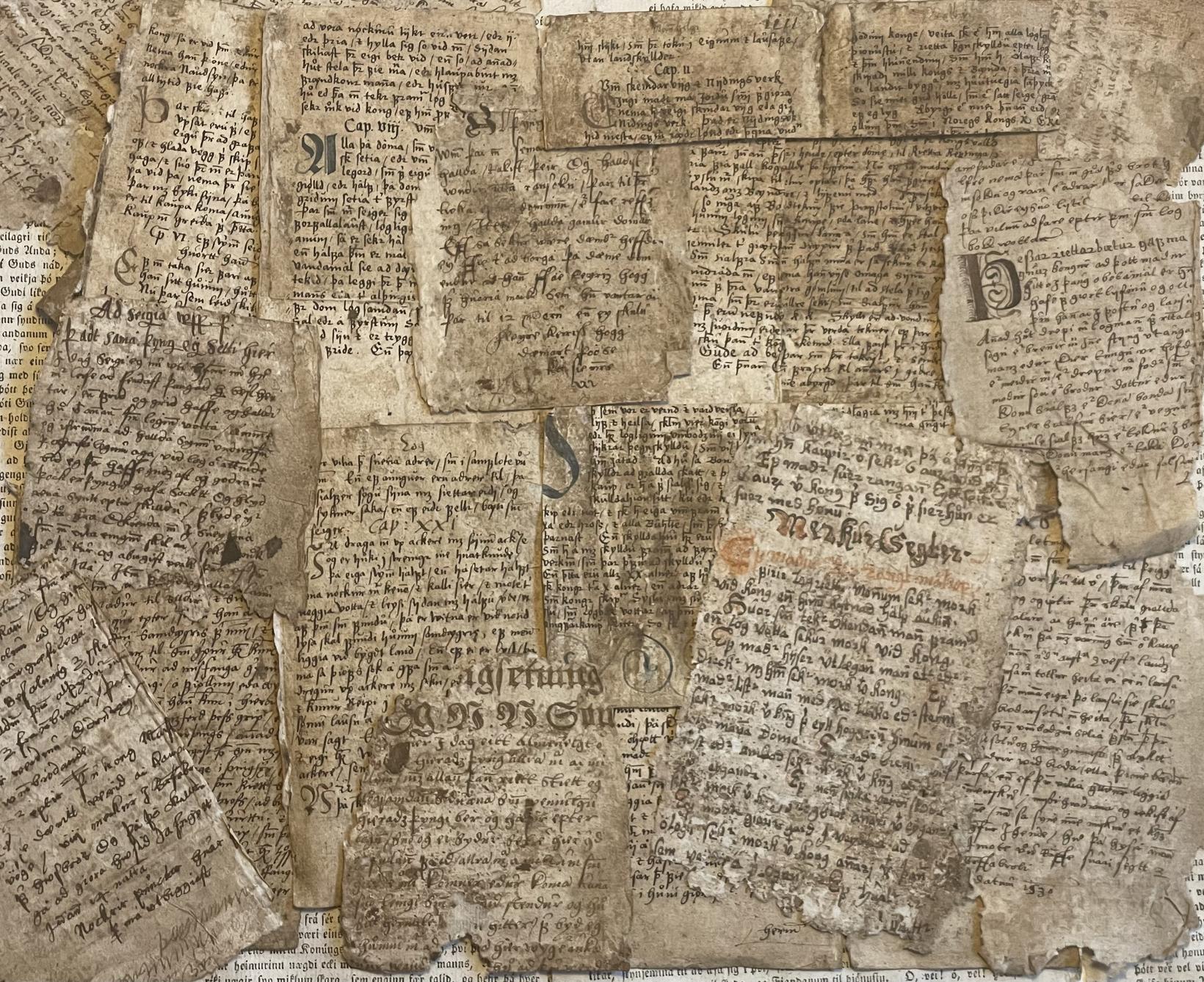

“The book needed repairing, and when I started to take it off the coat, pieces that turned out to be recipes from the ancient book of Jón were revealed.”

It was later discovered that the recipes were copied from the 15th century Jónsbók.

In the early 14th century, the codex of the Norwegian king Magnús Hákonarson’s lawbook was being cited (1238-1280) by Jón Einarsson, who in the spring of 1280 brought the book from Magnús to Iceland, but in the following year it was taken up by the Icelandic parliament.

Recipes in a context not known to all

Many people are familiar with the concept of recipes, especially in the context of cooking, baking, or knitting.

The term comes from the time women went from one town to another and made up a copy of each other. Recipes, it is said, are what the name implies when something is made up in two forms.

Eyþór says that writing from old manuscripts has been practiced for hundreds of years in Iceland.

“The subject matter of old songbooks or legends of Icelanders was often discussed, even written on paper. At the time, there was a lot of talk about, for example, titles of songs and Icelandic songs.

Invaluable find

Let us go back to Guðmundsson’s finding. He says that it was truly awe - inspiring, but little did he know what else remained to be seen. He explains:

“The gorgeously and lavishly decorated coat had been cared for centuries earlier, for both the top and bottom of the keel revealed repairs that were made in such a way that pieces of skin had been sewn into it to strengthen it.” The tell-alls were on recipes from old leather manuscripts.

Guðmundsson has a rule that he does not throw away anything he finds as it might be of use to him later.

“As I begin to clean the pieces of the leather, little by little something that seemed to me to be a sign appeared.

As I get to clean more, they become clearer until I realize what I had in my hands.

I was almost paralysed when I realized what kind of cultural value I was handling.

There, old manuscript pieces looked back for the first time in several centuries. ”

Visit to Árnastofnun

Guðmundsson took this very rare find to the Árnastofnun, which examined the pieces. Institute experts found that the pieces could be over 500 years old.

He says it was the fourth time that Árnastofnun had received such a find for investigation since it was set up in 1972 and took over the role of the Manuscript Institute.

Quite the incredible story, but has Guðmundsson come across anything more remarkable in his repairs?

“It’s not uncommon for you to come across old repairs when you’re going through the books and you’re restoring them.

When you take apart the books, you come across even 100 or 200 years of repairs. These repairs have made use of old materials to make old letters and other materials like that.”

A bookmark becomes a monument

In the midst of a coronavirus pandemic, he got a hold of an old hymnbook, which, Guðmundsson said, was not in itself particularly significant.

“I was impressed by the book’s cover and wanted to own it. As I was blazing through it, a note from it that had been sitting between pages falls on the floor.

The note, apparently written in 1907, was a communication from a farmer in one town that people would not come home to the farm while the measles epidemic was raging unless it was necessary.

A great coincidence to find such a thing in a pandemic that might as well have been one of the notes of our Covid team, 113 years before the coronavirus pandemic.

The note has probably been used as a bookmark at the time. It then comes to light over a hundred years later as a monument of that era. ”

Around 40 recipes

It’s only been about three months since Guðmundsson last found old recipes.

“I found, among other things, a number of recipes from John’s book and, for example, its title Óðalsbálkur.

These were over thirty recipe pieces, but I’m told that for example, the Óðalsbálkur is quite remarkable.”

The water both cleans and nourishes

“I take the book apart from A-Z and wash all its pages with water, both cleaning it and repairing it. Then I repair every page before I tie it back into the original cord.”

Our famous 12th - and 13th - century manuscripts are all written on parchment, that is, leather. It was only after 1580 that paper really began to replace parchment, and after the 17th century C.E., parchment had all but disappeared from the stage.

Paper of the day was made from often recycled fabrics such as flax, linen, cotton, or hemp. So a kind of linen paper can be washed like an article of clothing with water and then set aside for drying.

It was only after 1843 that paper developed the ability to not withstand getting wet at all, that is after it became produced cheaply mainly from pulp for papermaking.

After the restoration, Guðmundsson says that the book should be in good condition for several centuries if it is carefully considered and kept under proper conditions.

The craftsmanship Guðmundsson taught himself for the most part. He has gathered information from here and there.

“I have read both books and have studied videos, as well as accepted advice from specially trained specialists in this field.

I am quite moved by the fact that I have been able to hear, including from bookbinders and expert sources, that my repairs are nearly indistinguishable, including from the Árnastofnun itself.”

Grew up in an ancient printing site

Eyþór Guðmundsson was born in 1981. He is an expert in security and a licensed bodyguard. Like so many people, he has had many jobs in various sectors of the economy. He is, by the way, a pretty ordinary middle-aged man.

But what led a normal man of his forties to develop this passion for ancient books?

“You could say that my interest in preliterature started in childhood, but I’ve always liked old things.

The beginning came from when I first learned that the town where I grew up had one of the first printing houses in Iceland. In fact, it was the only printing house in the country for several years.”

Eyþór grew up on the farm Beitistaðir in Leirársveit in Borgarfjörður, and collects books mostly from there and from Leirárgarður, but also collects books from Hólar in Hjaltadalur, Skálholt, Hrappsey and Viðey.

“I love the books I read about them from Beitistaðir and Leirárgarður because I grew up there. My collection of books from these two printing houses is probably one of the largest in private collection in Iceland, counts over thirty books, ” says Guðmundsson.

Guðmundsson is quite adept at this work and he has a keen eye for detail. He is now working on making a model of the old farm of Beitistaðir, which is based on an old sketched picture.

“I thought of a new angle on the Instagram page of Old Icelandic Books. I wanted to make a model of the farm and then tell the story of the printing house. The project is getting much bigger than I expected, but I’m about to finish it.

The goal is to make a model of the old facilities as well and to display information on each site. Presumably, the farm Leirárgarður will be next in line.”

The treasures of the ancient books

Guðmundsson says his interest in ancient books goes far beyond the books themselves and their content.

I also take a keen interest in their history and, in particular, their demographic, anthropological and ethnological background. I look closely at the books and see things in them from their former owners that often give an indication of their position and status. I find this fascinating.

I also find it especially interesting and fascinating to handle books that have obviously been meticulously made at the time. Often the covers of the books are heavily decorated and every detail is taken care of,” he says, continuing.

“Some are carved with brass and decorated with gold, and the imprinting of paper was an art form in its own right.”

The books of the time included a number of what are called copper engravings, according to Guðmundsson, which he says were a method of incising images and shapes in copper plates covered with ink before they were laid on the paper.

“One of the many details that characterize these ancient books that have disappeared from contemporary bookmaking are the clamps,” says the ancient book collector.

Bookbinding clamps are a kind of clamps that were used to hold the books together and that played a big role in preserving antique books, especially larger works.

“But they did not have any less aesthetic purpose. So you can see that the bookmaking of those days was a major art form, and people either worked with the books from printing and binding to making covers, decorating, and goldlaying themselves, or specialized in on thing at a time and it often took years for people to become fully trained in their art.”

Bibles are a special favourite

One of the items collected by Eyþór Guðmundsson is Bibles, and he has a fairly large collection of Icelandic Bibles.

“I have six Viðeyjar Bibles, four Reykjavík Bibles, and then I have four foreign Bibles. It’s nice to say, for example, that my collection includes a Bible written in Arabic.

The Viðeyjar Bible counts 1,440 pages. Guðmundsson has restored two copies of it so far.

“Washing and repairing every page and tying it back into its original string is a lot of work and time consuming. When I was on vacation once, I began to restore the Viðeyjar Bible, and I worked non stop for 8 days 8 hours a day. Actually, I am about to start restoring the third copy of Viðeyjar Bible.”

Vídalínspostilla was the most widely read book in Icelandic history for nearly two centuries.

“I have every version of Vídalínspostilla from the beginning of time. I have made a point of having them.”

Long-lived Grallari

Of course, the librarian’s collection of ancient books will hide several copies of the so-called Grallari.

The original Grallari was published by Bishop Guðbrandur Þorláksson of Hólar in 1573. It was last published in 1779, and was widely used for some 200 years.

“I feel that you must have Grallari or the “Graduale: A simple Messusaungs Bok (a good book of psalms), and that they usually collect an ancient book of psalms. I have five copies of this fine book.”

Icelandic, yes please!

Guðmundsson says he only collects Icelandic antique books apart from collecting foreign books related to the history of England and Scotland.

“I have some more foreign antique books, of course, but I don’t collect them specifically.”

The irony of fate, though, is revealed by the fact that the oldest complete book in Guðmundson’s collection is a Bible in English, printed in 1595.

“Then I have a substantial amount of material that is older but can’t be defined as complete books.”

Guðmundsson says the community of antique libraries in Iceland is not very large, but there are some who collect such books.

He says that he does not know of many of the collectors involved in restoring the books; there are only a few of them that he knows of. But how do you restore an ancient book?

“ Have we... resolved to abolish both the supreme court and the law-making chambers? ”

One of the most remarkable of all in Eyþór’s collection is King Christian VII of Denmark’s decree from 1800 to abolish the Althingi parliament, along with a notice by Governor Magnús Stephensen about it.

When the Icelandic parliament, Alþingi, was suspended, the national supreme court in Reykjavík, took over the role of the Icelandic Legislature as the highest court in Iceland. In 1920 it was abolished and replaced by the Supreme Court.

In 1843 the king ordered the General Assembly to be reestablished, and in 1845 the assembly reconvened.

“Considering that the directive counts only 16 pages, it is my most valuable asset. This directive has been cited as a marvelous legal rarity and only two copies of it are kept in the National Library and only one copy of Stephensen’s advertisement.”

Hobby but not a career

Guðmundsson says that he never thought of making antique book restoring his prime career.

“It’s a hobby that is very rewarding in so many ways.

It's a hobby that brings endless learning and it's a hobby that's very rewarding for me.

That’s why I don’t want to make it a job, at least at this moment. Then it would no longer be a hobby,” says this remarkable antique book collector and one of the curators of the Icelandic Cultural Heritage.

/frimg/1/57/87/1578747.jpg)