Experts warn of higher costs, poorer service under new Health Inspection Plan

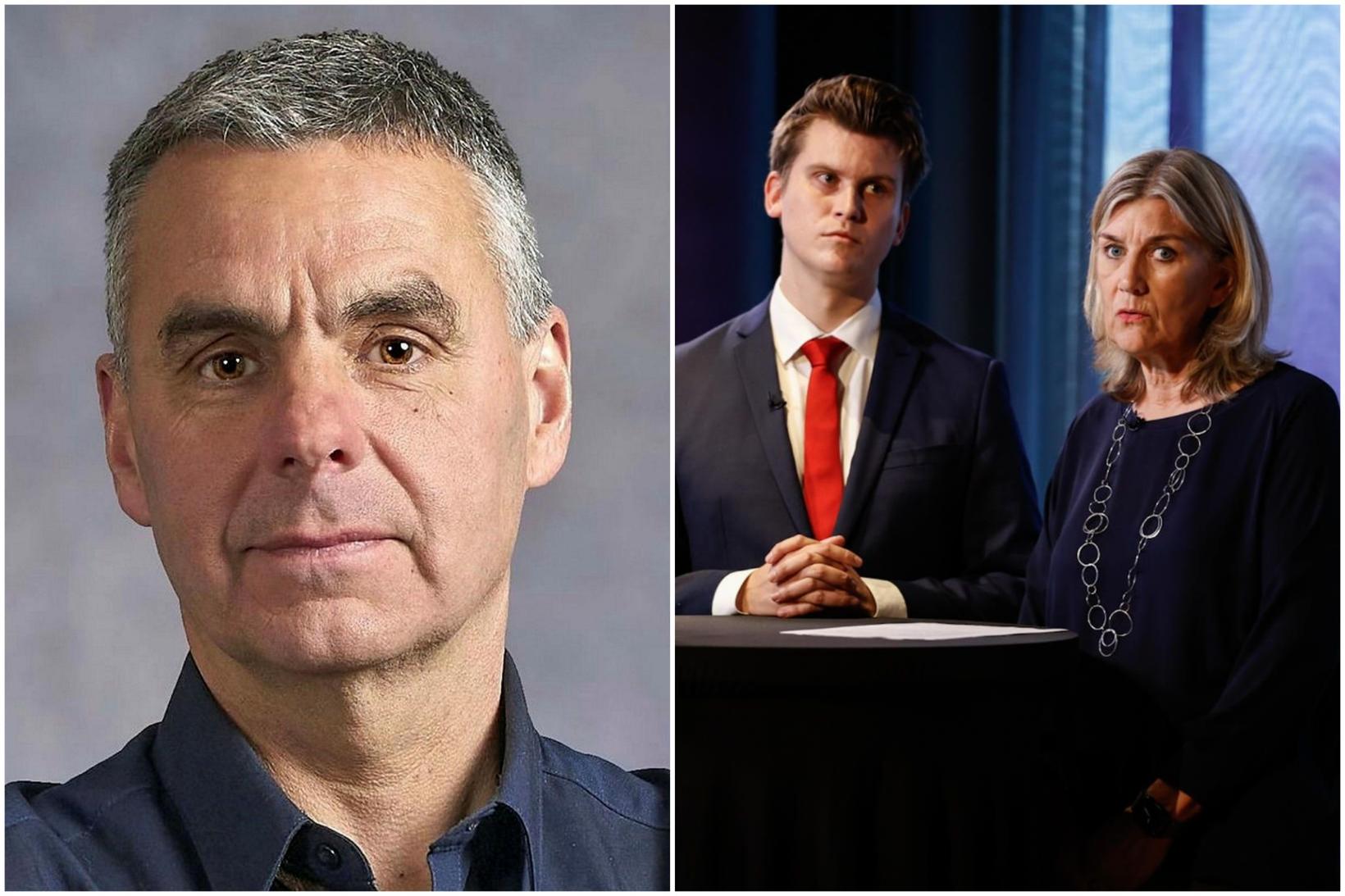

Tómas Guðberg Gíslason, director of Reykjavík’s Health Inspection Office, is part of a group of experts from regional health inspection districts who strongly oppose the ministers of environment, energy, climate, and industry’s plans to restructure the system overseeing public health, pollution control, and food safety. Composite image/mbl.is/Karítas

“These changes will not be without controversy,” said Jóhann Páll Jóhannsson, Minister of Environment, Energy, and Climate, during a presentation on a planned overhaul of Iceland’s system for health inspections, pollution control, and food safety monitoring.

His words quickly proved true. At the end of the meeting, Hörður Thorsteinsson, treasurer of the Association of Health Inspectors in Iceland and director of the health inspection office serving Garðabær, Hafnarfjörður, Kópavogur, Mosfellsbær, and Seltjarnarnes, stood up to voice his opposition.

Concerns over higher costs and declining services

Thorsteinsson said that a group of experts within Iceland’s health inspection system strongly opposed the ministers’ and government’s plans, arguing that the changes would not benefit the operations or the public.

Under the proposal, the current nine regional health inspection districts and two national agencies would be consolidated into just two national agencies: the Environment and Energy Agency and the Icelandic Food and Veterinary Authority.

The group expressed deep concerns that the restructuring would lead to poorer service and higher costs for both residents and businesses, as well as for municipalities. No cost analysis has been presented, they said, only a note that a new computer system—expected to cost hundreds of millions of krónur—would be required.

Lack of consultation and collaboration

In an interview with mbl.is , Tómas Guðberg Gíslason, director of Reykjavík’s health inspection office, said the group believes the government’s approach has been fundamentally flawed, criticizing what he called a lack of dialogue and cooperation with stakeholders.

“There has not been sufficient communication or collaboration with municipalities, the Association of Local Authorities, or other stakeholders. For example, this very meeting was announced with only two hours’ notice,” he said.

He pointed out that the steering committee’s report, released on the same day, was dated June, yet no one—including the committee members themselves—had seen it beforehand.

Hörður Þorsteinsson, treasurer of the Association of Health Inspection Districts, stood up at the end of the meeting to emphasize that a group of experts within Iceland’s health inspection system strongly oppose the ministers’ and government’s plans, saying the changes would not benefit the operations. mbl.is/Karítas

“Professionally wrong” decision

According to Gíslason, the group believes the ministers’ decision is professionally incorrect and potentially harmful for both residents and businesses.

“There is a clear lack of understanding of the work and role of health inspection offices. These offices do far more than routine inspections. They also monitor rivers and lakes, air quality, noise levels, and handle complaints and planning consultations in close cooperation with municipalities,” he said.

The group dismissed the ministers’ statements acknowledging that health offices have broader duties, arguing that the government’s real goal is to centralize routine inspections—currently the only services municipalities can charge fees for—while leaving costly tasks, such as environmental monitoring and complaint handling, with the municipalities.

No simplification, only more complexity

Gíslason warned that the plan would not simplify processes but rather add layers of complexity.

“Under this proposal, two different national agencies would handle inspections. For example, a preschool with a cafeteria would now require inspections from both the Environment and Energy Agency and the Food and Veterinary Authority, whereas today a single local health office handles everything,” he explained.

When asked whether the two agencies might eventually be merged, he noted that this had already been tried in the past under the former State Health Protection Agency.

“It would just be going in circles,” he said.

He also pointed out that state fee schedules are generally higher than those of municipalities, raising fears that the changes will lead to higher costs for businesses.

Furthermore, Gíslason said that increasing the distance between inspectors and local operations would reduce understanding and responsiveness to local needs.

Better to improve the existing system

Gíslason argued that concerns raised by ESA, the EFTA Surveillance Authority—which the reforms are partly intended to address—apply almost exclusively to companies overseen by the Icelandic Food and Veterinary Authority, an agency he said has failed to meet its legal obligations.

“It is illogical to try to fix that problem by transferring all inspection responsibilities to the very agency that hasn’t been fulfilling its duties,” he said.

The group believes the disruption would be enormous and that it would be far more sensible and professional to strengthen the current system by having the two national agencies fulfill their legally mandated coordinating roles—something they have not been doing.

“That would have been a much wiser approach,” Gíslason concluded, “ensuring that local knowledge is preserved and that services remain strong, consistent, and effective.”