"The marital bed becomes a battlefield"

Director Þorleifur Örn Arnarsson and visual artist Erna Mist Yamagata are creating their world in a new home. They met over a year ago and are now working together for the first time on Tennessee Williams’s play Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, which will premiere at the City Theatre on December 28. The couple is expecting a child in January, but Arnarson has a 13-year-old son from a previous marriage.

Arnarson directs Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Yamagata designs the set and costumes. When asked if working on the work is fulfilling an old dream, they say yes.

“This American neoclassicism has always appealed to me. Tennessee Williams belongs to this artistic explosion that occurred in American playwriting in the middle of the last century, but modern television series and films are rooted in this time. For example, his works have striking parallels with TV shows like Succession and Yellowstone. This is a showdown with the tyranny of the father and power structures. The discussion about staging this work in Iceland started at the same time we were getting to know each other. Then it turned out that this is one of your favorite works,” Arnarsson says and looks at Yamagata and she agrees.

“The birth of this project came about in our conversations about the themes, the threads, and the message of the work to the present,” he says.

“It was not decided that I would participate in the production,” Yamagata says.

“I had already declared that I wanted to work with you,” he says.

“The amazing thing about this work is that it is performed in real-time, in one evening, in one room – but despite its limited framework, it manages to address the biggest questions of existence,” Arnarson says.

Like what questions?

“There is a fight over the inheritance – which in a metaphorical context is the fight over the future; who gets to be the holder of the future. That is why it is reminiscent of Succession. This is a fight between brothers over their father’s wealth, but both of their wives are driving the fight. One brother and his wife have five children, while the other is childless – which puts them in a worse negotiating position, so they are forced to resort to extreme measures. The father has been ill for a long time and is in the process of making a will. On this one evening, a showdown begins, a joint attempt by all of them to separate the truth from the lies. This is a family drama where everyone has to fight for their point of view, their vision of life, and their existential property rights. We watch a family potentially broken apart because they cannot unite around a central vision of life,” Arnarsson says.

“The work tells a specific and broad story at the same time, because the characters are the embodiment of a larger system. The conflict between husbands and wives is a conflict between the sexes, the conflict between fathers and mothers is a conflict between generations, the conflict between brothers is a conflict between classes,” Yamagata says.

“All the characters in this work act terribly and immorally at some point, but then an unexpected perspective appears that justifies, or at least explains, all of this. The work constantly opens new doors that make you question the opinion you formed a while ago,” he says.

Isn’t that just a bit like how people really are?

“It’s so difficult in social discourse these days how we tend to take one negative event from a person’s life and apply it to their entire life. People are not good or bad. The context plays a big role. In the theater, you go through empathy training where you start by sympathizing with someone, then you start to despise that person, and then you start to feel sorry for that person. The experience draws a spectrum of the complexity of the human being, which is inherently complex and intricate. In our strongest moments, we are incredibly beautiful and in our weakest moments we can become unforgivably cruel,” he says.

The double bed is a battlefield

How do you interpret the set and costumes in this work?

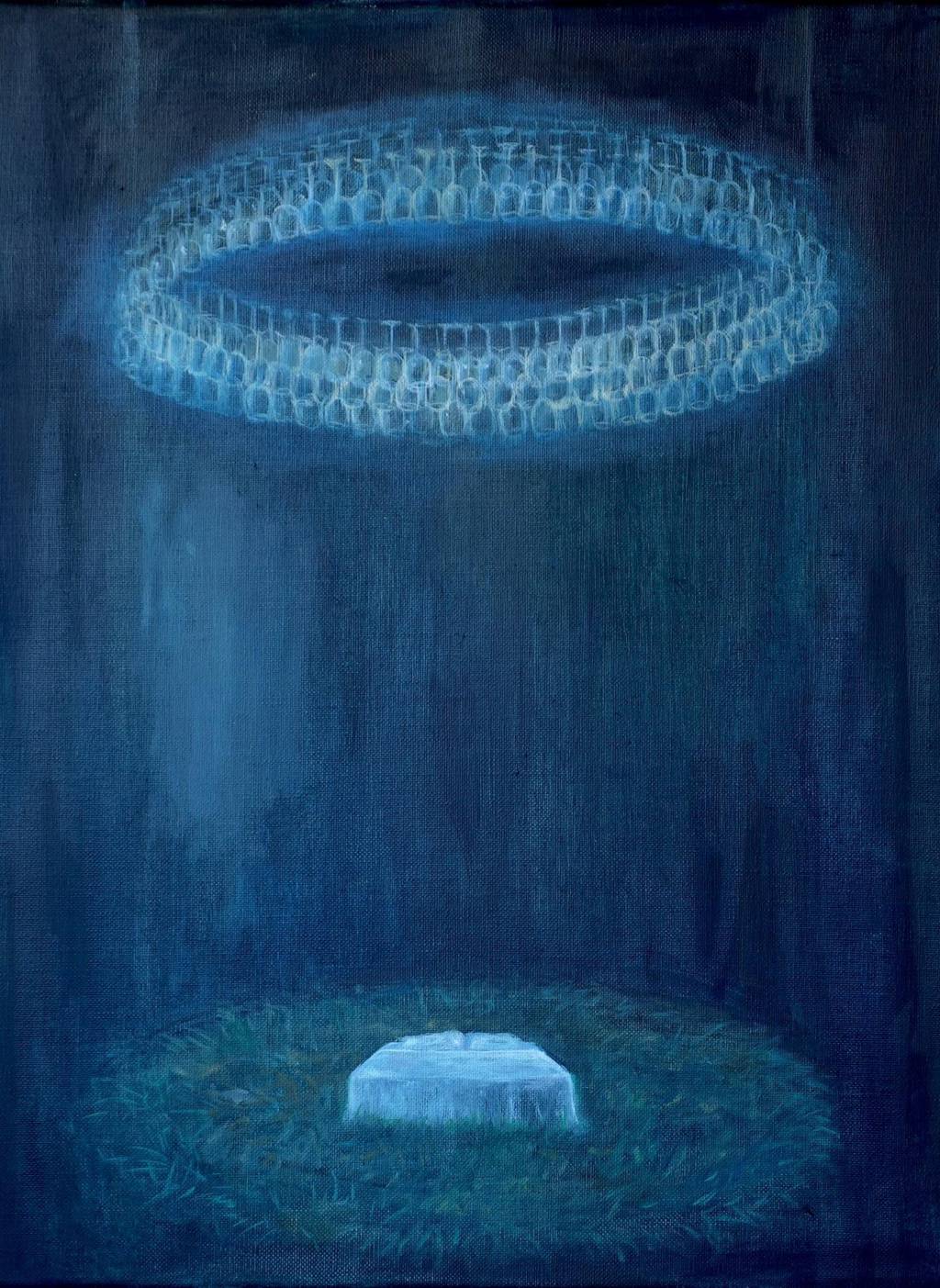

“I conceived the set like my paintings. Instead of imitating a real place, I collected visual references and built a dreamlike visual world from them. In the middle of the stage is a double bed and the audience sits in a circle around it. Above the stage hangs a chandelier made of weeping wine glasses. "Instead of drawing a naturalistic situation, I read the work and looked for a poetic core, so that the heart of the work could burst out into metaphor," she says.

"The marital bed becomes a battlefield, where the audience sits around the characters and watches them like gladiators in a pit," Arnarsson says.

"The bed is there as a constant reminder of the children they did not have," she says.

"This work is somewhere between a family tragedy and a thriller and is one of the best-written confrontations between people I've ever read in a play. It's so fun to go into these big scenes. You become so grateful for having a relatively beautiful family life," Arnarsson concludes.

/frimg/1/59/16/1591663.jpg)