Overturned a false confession in England

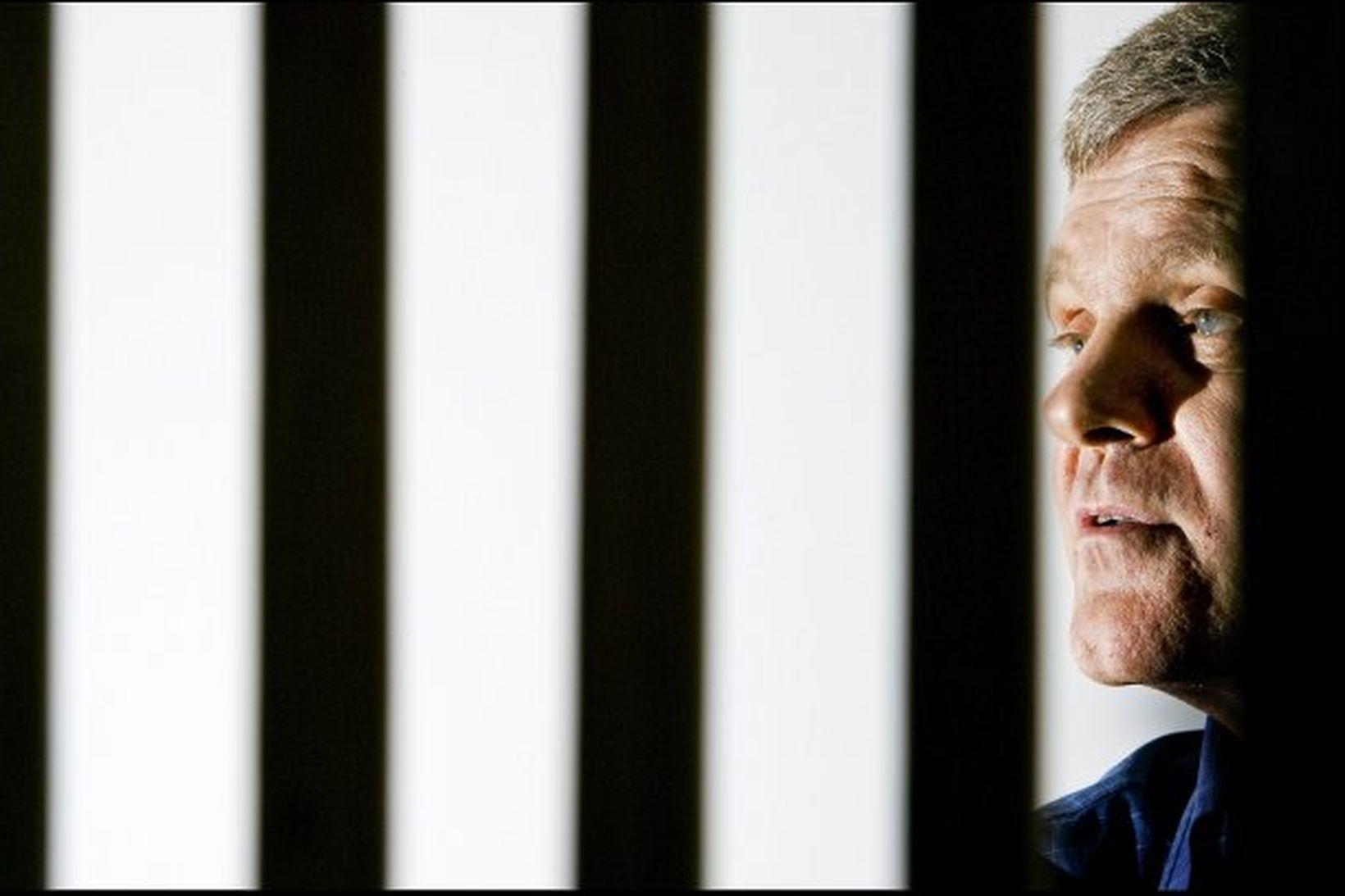

Gísli Guðjónsson, professor emeritus of psychology at King's College University in London, has gained a reputation around the world as an expert in false confessions of defendants and involved in high-profile criminal cases. He himself has not lived with the view that the picture shows, but Kristinn Ingvarsson, former photographer of Morgunblaðið, took the picture with his skillful artistry through the back of a chair in the professor's home. mbl.is/Kristinn Ingvarsson

"In 1991, I was asked to give an IQ test to Oliver Campbell, there were two of us who came up with this, a psychiatrist and I, and my part was somewhat limited," says Gísli Guðjónsson, professor emeritus of forensic psychology at King's College University in London and expert in false confessions, in an interview with Morgunblaðið about a more than a three-decade-old case that turned an innocent man's life upside down.

It was at the end of July 1990 that two young black men broke into a grocery store in Hackney, London. At gunpoint, they demanded whatever money the merchant, Baldev Hoondle, had on hand. A scuffle ensued between the merchant and bystanders, and one of the robbers shot Hoondle dead at close range.

During his escape, the other miscreant lost his British Knights baseball cap, and a slow-moving police investigation ensued. It wasn't until the following year, 1991, that police believed they had found the robber who shot – Oliver Campbell of Stratford. Oliver Campbell was young, like those who committed the robbery, and his complexion was the same. The police believed that the conclusive evidence was that shortly before the robbery he had bought the same kind of baseball cap found at the scene.

No witness identified Campbell

There were several witnesses to the robbery, including the victim's son who looked directly into the shooter's face inside the store. He did not identify Campbell in any of the three indictments. No other witness identified him either. The witnesses agreed that the killer was older, Campbell was nineteen years old. They also agreed that the perpetrator was under 180 centimeters tall, and Campbell is almost 190.

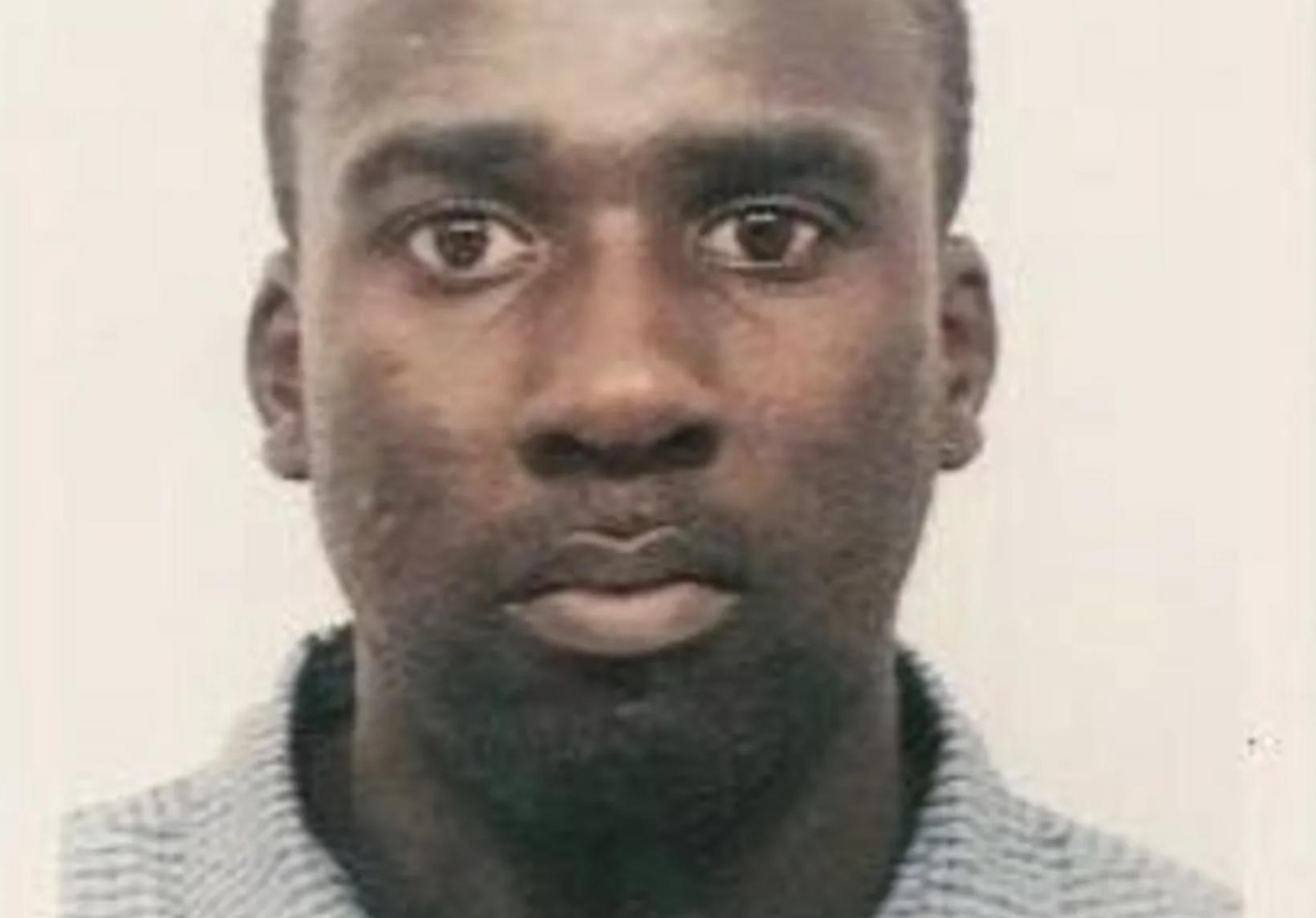

The police set out to convict Oliver Campbell, they were running out of time in a homicide investigation, and the people demanded a guilty man for trial and punishment. Photo/Metropolitan Police in London

"When I looked at the hearings, I didn't like it, I felt as if he had been forced," Guðjónsson says, but Campbell suffered a brain injury in childhood and his IQ was measured at 73 points. He therefore had to defend himself against the tough police interrogators who had already determined his guilt. A homicide investigation had dragged on, a black man who had worn the same hat had to be a cold-blooded killer. The police simply ruled out other possibilities.

"I looked at these fourteen interrogations, but there was no sign of it. No one wanted to hear that the police had done something wrong," continues the professor, but Guðjónsson has earned a reputation around the world for his perceptiveness in evaluating the testimony of defendants who testify, including hitting the nail on the head in two long-standing cases in Norway, of young Birgitta Teng and the Baneheia case in Kristiansand. In both cases, the police had found their defendant - one of which was innocently imprisoned for 20 years.

Thirty years later, in 2021, Guðjónsson was contacted and asked to look at Campbell's case again. The re-admission committee had then decided that the case should be reviewed. Campbell was then a free man – having served eleven years for shooting the merchant in London. However, he was by no means free from the yoke of having been incarcerated for what was a third of his life when he was released.

"I've been a pioneer in working on these cases and trying to improve the science, looking at what happens in interrogations when people confess to something they didn't do." mbl.is/Árni Sæberg

"I was asked to look at the case again in the light of the science now and submitted a more than forty-page report which, among other things, was based on the methodology that developed following the Guðmundur and Geirfinnur case in Iceland. The case then went to court on February 29, where I gave an oral statement that took about two hours. Science has developed so much in these thirty years, it was not very far in 1991 and you can never get ahead of science," he says about his part in the re-opening case.

What happened after the tenth hearing?

He says several studies have been conducted on the statements of people who have given false confessions. "I've been a pioneer in working on these cases and trying to improve the science, looking at what happens during interrogations when people confess to something they didn't do. Many factors have to be taken into account and people's backgrounds have to be looked at. "Oliver Campbell had suffered a brain injury, and factors such as the fact that no DNA from him was found in the hat also need to be looked at," explains the psychologist.

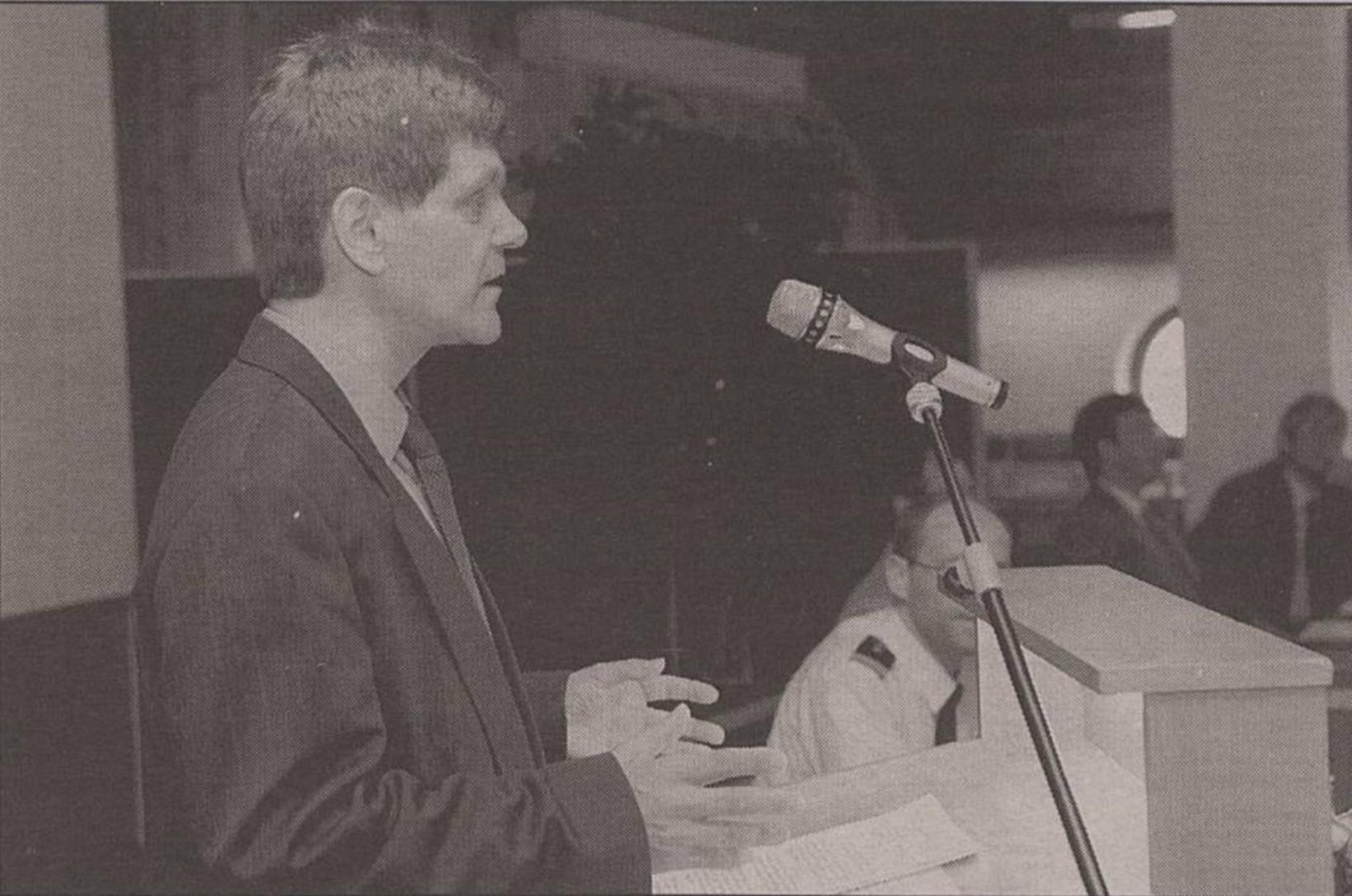

Press conference of the Minister of the Interior and the working group on the Guðmundur and Geirfinnur cases in March 2013. The working group that investigated the Guðmundur and Geirfinnur cases said beyond a reasonable doubt that the testimony of all those who were sentenced in the case had been unreliable or false. Mbl.is/Rósa Braga

After Campbell's tenth hearing in 1991, there was a turning point in the case. "Then his lawyer goes home and Campbell plans to rest after the hearing." The police then want him for more questioning. His foster mother is then there and he just wants to go home. He saw nothing but that he would remain in detention unless he confessed," Guðjópnsson says.

He says it's common for people struggling with mental challenges to believe that if they confess, they'll just get to go home. "This was his way of thinking and I have seen this many times before. He was stressed and under a lot of pressure and had limited help. The police method was to read his reactions over and over and point out what they thought he had done. He was led on, but the court did not want to impose anything on the police at the time," says the psychologist.

"The system always protects itself"

During the retrial, however, the court was not able to oppose the theories as they had developed. "So this is a big event for science, even if they tried to screw me up on something, they couldn't screw up the science that was there." A big milestone has been reached there, the system is always rigid, the system always protects itself and often it is a great struggle, you must never give up," says the professor.

"What's better nowadays about hearings is that everything is recorded, you know exactly what is said and done during hearings. The only thing we don't know is what happened between Campbell's hearings number ten and eleven in 1991," he recalls from all these years ago, and the dark shadow of a legal system that made an overzealous effort to bring the people the guilty party at all cost. Even if he was not guilty.

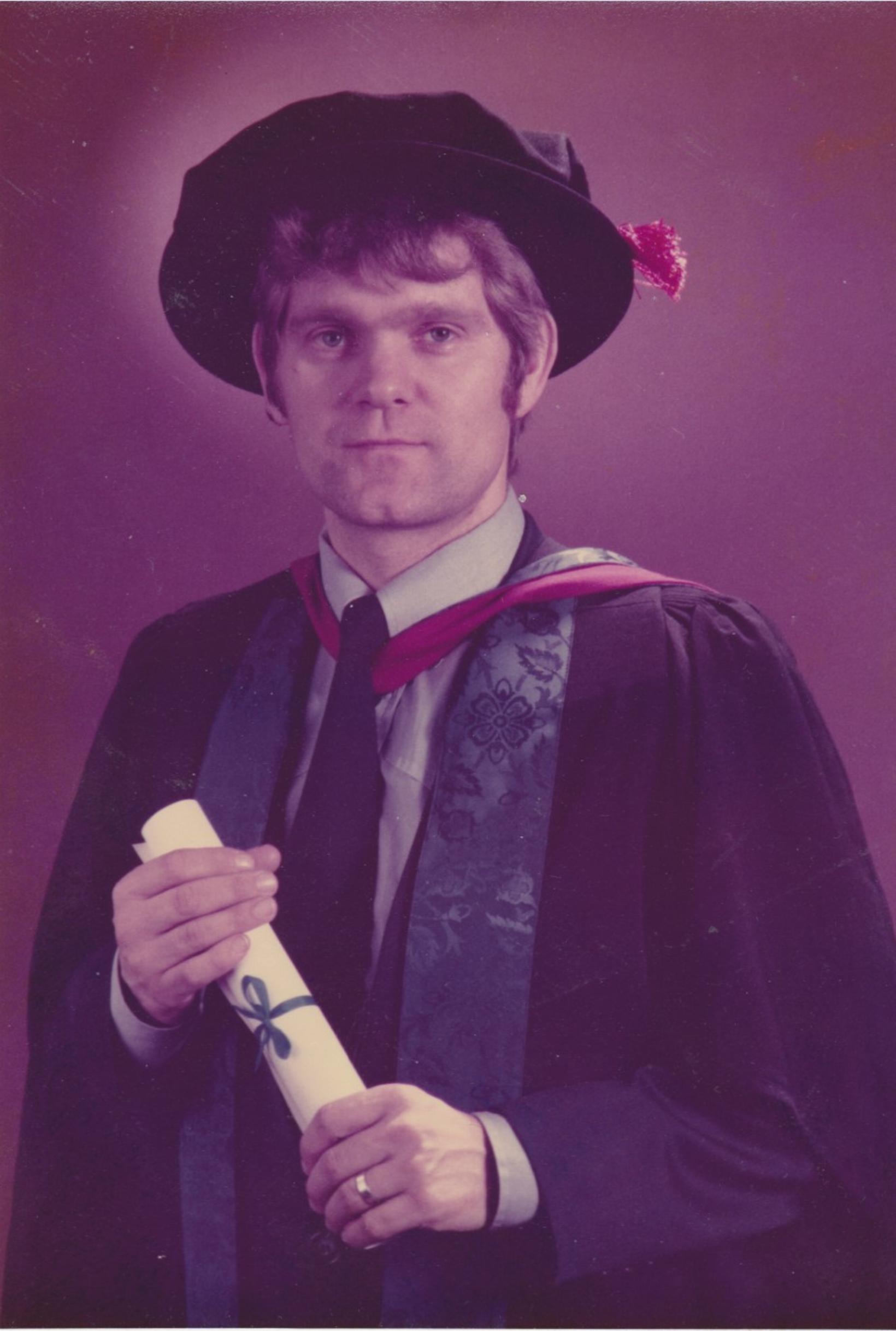

Gísli upon graduation from a doctoral program in the UK in 1981. His PhD thesis dealt with lie detection. Photo/Sent to mbl.is

"Campbell had already denied everything with the lawyer present. Then something happened, and it is not recorded what it was. Suddenly he wants to confess. He just thought about what he could do to get home, he just wanted to get home. He didn't think any further, just about what he could do to get rid of this," Guðjónsson says, whose case has been discussed in the world's biggest media for the last few days - a man who was robbed of a large part of his life by the British legal system.

How do you think the working methods of the police during interrogations in criminal cases, as you know them, have developed these decades, for example from the Guðmundur and Geirfinnur case at the time?

"Naturally, this has completely changed," the professor replies, "it was a big phase to deal with the Guðmundur and Geirfinnur case when it came to that, it was very harsh, and I am proud to be an Icelander," Guðjónsson says, referring to the final end of the most protracted judicial cases in Iceland's history that acquitted all involved. Guðmundur and Geirfinnur were never found.

Shortage of specialists in this field in the world

"In Britain, all the research that's been done and the teaching that's been done has changed the way the police work, you don't see a lot these days of poor police practice, I don't get as many cases. Naturally, I'm retired and I'm not looking for cases, but they just come to me and it's hard to turn them down when you might have been involved in the case in 1991. The trouble is that there is a lack of people in the world, experts who have experience and can see the issues in context, this requires a lot of experience. You always have to look at the case as a whole," Guðjónsson says, and the professor's interest in the studies is reflected in his words.

He does not rush to assess the veracity of a statement and reiterates the importance of looking at the whole picture instead of focusing only on individual elements. "I get quite a lot of cases and I try to turn down everything I can," the professor says wryly, "but there are times when I can't think of anyone else who could solve a case if it's complicated," he continues, points out again that there is a shortage of experts in the world, trained psychologists or psychiatrists with this specialty - false confessions in criminal cases.

How did it come about that your path led to such a limited specialty of studies at the time?

"I worked in the police, I was a summer police officer, and it was the experience I got there that got me into this," he answers, recalling the long-ago time when he was a summer police officer in the early 1970s, in the summer of 1973 "I'm a scientist by nature and I was always connecting science with police work," says the professor, who at that time had just started studying psychology at Brunel University in Middlesex, London.

Guðjónsson held a course for police officers in Reykjavík in August 1997 about his studies, which countless of his students at King's College in London have studied at his feet. He says more experts are needed in the field of false confessions. mbl.is/Ásdís Ásgeirsdóttir

Conducted research on Breiðuvík

"I was also in the police in 1975 and '76 and came to the Guðmundur and Geirfinnur case, I met five of the six who were defendants there," he continues when this old - and yet still new to a certain extent - court case comes to mind, The gloomy Síðumúli prison, the "Leirfinnur" statue and investigation methods that would never have survived to this day, perhaps the darkest valley that the Icelandic legal system has passed through since alleged witches were drowned and wizards were burned in the darkest Middle Ages at the instigation of Reverend Páll Björnsson, a priest in Selárdalur Valley, and more people in power.

"I was there at the time and became interested in interrogation methods and murder cases. It was an invaluable experience that I got from the police and these were good times in that respect that I learned so much," the psychologist recalls of the instructive time in his life half a century ago. Something that has helped him become one of the world's leading experts in false confessions - you don't pick that up off the street.

Guðjónsson is the brother of Guðmundur Guðjónsson, a former superintendent who started working in the police after Guðjónsson left the street police in 1973, but he was a detective in 1975 and '76. "He was famous there," he says of his brother, "I was interested in traveling and having adventures, but he had no interest in that," says Guðjónsson, laughing good-naturedly.

In 1974, Guðjónsson worked for six months at the Reykjavík Social Welfare Institute and then carried out research on Breiðuvík, the infamous orphanage for boys that was established there in 1953 and decades later became the subject of large compensation payments by the Icelandic government to former residents who had been abused there, some of whom were damaged for life.

"Everyone was talking about what a good organization this was, but I asked myself 'is this such a good organization?', then the scientist in me came out. Then I researched it and it turned out that this home was not as good as people thought."

His report on the case was labeled confidential and simply put in a drawer at the time - in 1974. "Then some journalists found it thirty years later and everyone knows what happened next," he says.

Always meant to come home

As mentioned earlier, Guðjónsson began his university studies in psychology at Brunel University, but he completed his master's studies at the University of Surrey in Guildford, where he completed his master's and doctoral degrees, the latter in 1981, but he had completed his official degree in clinical psychology in 1977 and worked at the same time as his doctoral studies at Epsom District. Hospital, from 1977 to 1979, and later the Institute of Psychiatry at London University, from 1980 to 2011.

"I always wanted to go home with my knowledge, I just wanted to get an education and learn, it was also good to be at home and be able to work in the police force to raise money for my studies, these were very exciting years and this experience made me the scientist that I am today," Guðjónsson says, who discussed lie detectors in his doctoral dissertation, and, despite everything that has been said, his career is far from exhaustive.

"So now I was a messenger at Morgunblaðið when I was twelve years old, Morgunblaðið is in my heart. There was once a photo of me in Morgunblaðið that photographer Sveinn Þormóðsson took, and it was a very exciting time as well," concludes forensic psychologist Gísli Guðjónsson, a scholar who has uncovered several false confessions for decades, and he did so in case discussed here, the case of Oliver Campbell who would not have spent eleven precious years as a young man behind bars had the science been sufficiently advanced in 1991.

/frimg/1/57/87/1578747.jpg)