Earthquakes on Reykjanes Peninsula Explained

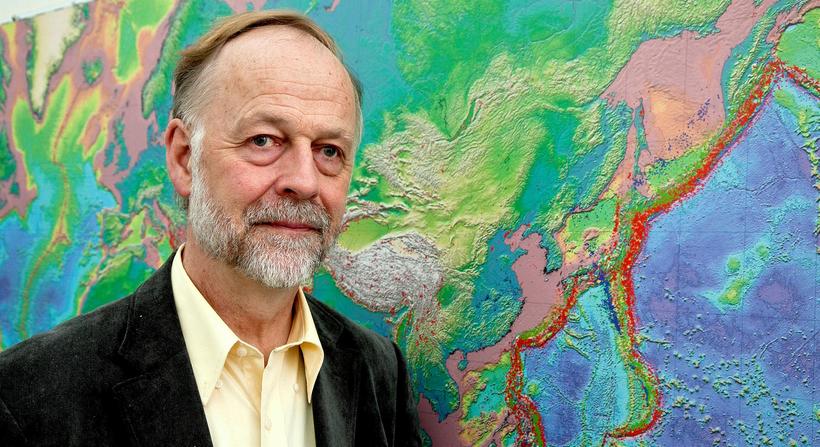

“Last year and so far this year, there has been a major increase in seismic activity on the Reykjanes peninsula,” Páll Einarsson, geophysicist and professor emeritus, tells Morgunblaðið , speaking of the area in Southwest Iceland that has seen thousands of tremors since February 24. He believes this jump in seismic activity is due to magma having reached the earth’s crust.

“It is not usual for seismic activity to take such a large jump over this long a time period,” he states. “Tension has been gradually accumulating. Then, some of it is relieved when part of the area exceeds the rupture limit, and that results in an earthquake. As soon as liquid, in this case magma, is present in the earth’s crust, then [the crust] weakens, and anything breaks that can possibly break.”

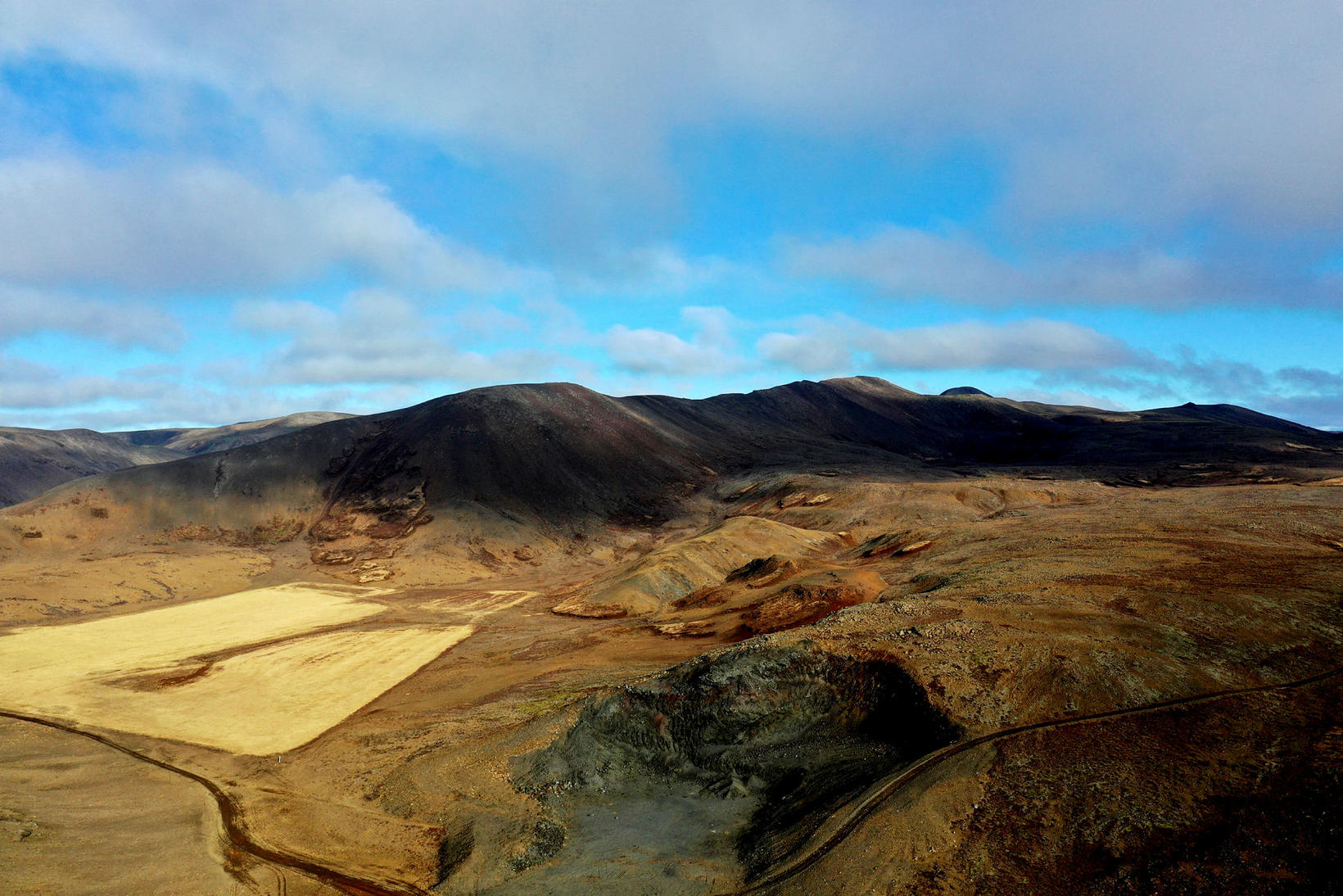

This series of events did not start last month, but in December of 2019, when a swarm of earthquakes hit Fagradalsfjall mountain. Until then, the mountain had not been in the limelight. Therefore, this swarm of earthquakes was regarded as a coincidence.

Subsequently, magma intrusions occurred near the mountain Þorbjörn, by the town of Grindavík, last year. Those appear to have greatly affected the area.

“Then, we had a tiny [magma] intrusion on February 24 this year, which triggered the big earthquake [of magnitude 5.7], and after that, all hell broke loose,” Páll explains.

He believes the current earthquake swarm can be explained by the interplay of tension, which has accumulated at the tectonic boundary of the North American and the Eurasian tectonic plates, (which lies across the Reykjanes peninsula), and the magma intrusion.

“We are familiar with magma dykes of this magnitude, and there were several such during the Krafla eruptions.” [The Krafla eruptions in Northeast Iceland began in December of 1975 and lasted until September, 1984.]

“They were not accompanied by seismic activity on this scale,” Páll continues. On the Reykjanes peninsula, he states, “the energy in the earthquakes originates in the tectonic plate movement, while the magma dyke works as a trigger on the whole system and makes everything break that has any tension at all.”

So far, there are no signs of a magma chamber forming under the Reykjanes peninsula. The magma appears to rise through a channel and accumulate in the magma dyke alone. Páll likens the shape of the magma dyke to table top, with a thickness of 1-2 meters, which stands upright. The upper edge is at a depth of 1 km, and the table top extends to a depth of 4-5 km.

While the magma dyke is not growing longer, it is likely getting thicker. But how likely is the magma to rupture the roof and reach the surface?

“That’s just a question of amount of magma and how long it continues to flow,” Páll replies. “It could possibly stop. There are examples of that. We had 20 such magma dykes during the Krafla eruptions, and nine of those reached the surface, resulting in an eruption. The largest ones did not.”

He adds that according to physics, part of the magma in the magma dyke must have started solidifying. It takes a few days or weeks to solidify in a magma dyke of this thickness. It’s been three weeks since the magma flow began, so the thinnest parts of the magma dyke must have solidified by now.

/frimg/1/57/87/1578747.jpg)