Divers explore 17th century Dutch shipwreck in Iceland

The oldest known shipwreck around the coast of Iceland is currently being researched by marine archaeologists as part of a Rannís funded research project examining the archaeology of the Danish trade monopoly period 1602-1787.

The wreck was originally discovered in 1992 by two divers, Erlendur Guðmundsson and Sævar Árnason, in the old harbour of Flatey Island in Breiðafjörður along the west coast of Iceland. A survey project carried out on the wreckage in 1993 by Dr. Bjarni F. Einarsson for The National Museum of Iceland uncovered a significant amount of 17th Dutch century pottery associated with the wreckage and an area of approximately 35 square metres of the wreck was recorded.

Flatey Island was previously a significant trading harbour and transit point for traders over the centuries in Iceland.

The ship in question is believed to have been a Dutch armed merchant ship named Melkmeid ( Milkmaid ), which is believed to have sunk in Flatey harbour in the autumn of 1659. The ship had been rented by Jonas Trellund, a Danish merchant, to trade with the Icelanders on the west coast that year and it was likely crewed by mostly Dutch sailors.

While at anchor in Flatey harbour, just as it was due to sail back to Europe with a full cargo of fish on board, a fierce storm blew up and caused it to catch fire and sink. All but one of the 15 crew members on board survived.

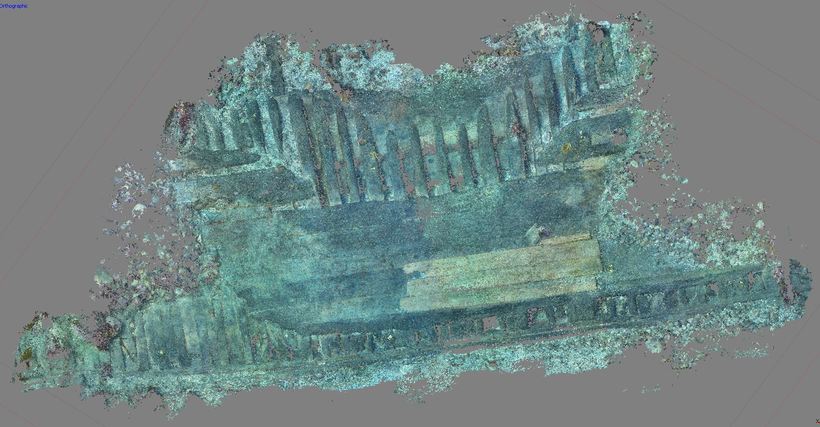

Screenshot of dense point cloud stage of 3D photo-grammetrical model of Melkmeid shipwreck. Photo: Kevin Martin / Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed

According to the Icelandic annals the remainder of the crew salvaged what they could from the sinking ship and remained on Flatey Island that winter being looked after by the locals there. The next spring in 1660, the annals note that they built another ship from the wreckage of the Melkmeid and sailed home.

When the Melkmeid sank the whole ship was not submerged at the same time. The upper decks are likely to have been sticking out of the water for a while. It is likely that wood and other resources from the ship were salvaged by the locals on Flatey as these would have been very scarce commodities back in this period.

During the discovery of the Melkmeid in 1992 a second younger shipwreck was idenitified in the same location partly covering the Melkmeid's remains. Einarsson’s research identified this to have possibly been the Danish schooner Charlotte which sank in 1882.

The current research project was led by Kevin Martin, a marine archaeologist and PhD student in archaeology at the University of Iceland. He was joined by two Dutch marine archaeologists, Thijs Coenen and Johan Opdebeeck, from the Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency as well as a marine biologist, Fraser Cameron, from the University of Iceland.

In May, the team carried out a 7-day intensive underwater survey of the Melkmeid remains. A larger area of the wreckage was uncovered than had been in 1993 and a number of dendro-chronological oak samples were taken for further specialist analysis. The results of this should enable the archaeologists to confirm conclusively that the wreckage is that of the Melkmeid and also when and where the wood for the ship had been originally cut.

A large part of the project was devoted to conducting a 3D photo-grammetrical recording of the ship remains. This was the first time this recording technique has ever been attempted underwater in Iceland to record archaeological remains. The final results of this which include a 3D model creation are still currently being processed but initial findings have been very good.

The team also accessed the archaeological preservation of the wreckage and in order to slow down its natural deterioration they covered the exposed parts of the wreck with a protective fabric. A follow up project involving archival research on the Melkmeid in the Netherlands is planned in the autumn.

Kevin, who originally comes from Ireland but has lived in Iceland for over a decade, says “the Melkmeid project really highlights this undervalued and under researched part of Iceland’s history.

Compared to the Netherlands and Sweden underwater archaeological research in Iceland is still well behind but projects like this one, show that it is possible to carry out this type of research here even in the freezing cold North Atlantic waters and how much we can really learn from doing projects like this.

Shipwreck remains can survive very well in Icelandic waters and there is definitely a lot of potential to do more underwater research around the coastline. Given the necessary funding the future is bright for marine archaeology here.”

/frimg/1/53/30/1533092.jpg)